|

book reviews

More Rhetoric booksreviewed by T. Nelson |

|

book reviews

More Rhetoric booksreviewed by T. Nelson |

Godine, 2011. 253 pages

Reviewed by T. Nelson

trong in the force he is.

trong in the force he is.

A dear friend, you are not.

A horse is a horse, of course of course.

What does he do, Clarice? What is the first and principal thing he does, what

need does he serve by killing? He covets.

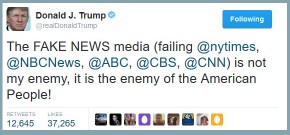

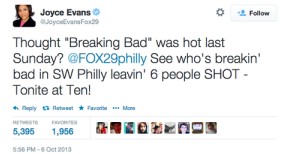

The above sentences are all examples of rhetoric: the art of arranging words to make an argument memorable. Rhetoric isn't just for demagogues, politicians, and cannibals. It's also of immense use for your everyday tweeter. For where is there a man, woman, or child who has not used some rhetorical device? (This is an example of erotema: a question that does not call for a reply.) Rhetorical flourishes often turn up where least expected, as in the following example:

Their names—anaphora, epimone, isocolon, anastrophe, asyndeton—may be unfamiliar to your average humble bloggers who spend their days grinding out mindless drivel, but learning them would be a good thing. Just as metaphor is the enemy of finger-wagging, and steely passion the (ellipsis) enemy of mindless F-bombing, so soaring rhetoric is the enemy of dreck.

These devices are powerful, and Farnsworth warns us not to overuse them, but it's hard not to. He gives an example of Dickens, an example of Burke, an example of Lincoln, and an example of Churchill. It is good for the writer, it is good for the reader, and it is good for the collector of interesting quotes (anaphora).

Of course, politicians have no monopoly on rhetorical flourishes. Many if not most tweets are incomprehensible gibberish, but occasionally one finds a rhetorical flourish. Here's an example of erotema: a question that does not call for a reply (from here).

Just as too many F-bombs make you look like a flaming a*****e, too much rhetoric can make you look like a thundering Calvinist. Indeed, one F-bomb in a lifetime may be too many, and one lifetime in an F-bomb (chiasmus) is, well, it doesn't even make sense (metanoia), unless your name is J.F. “Ask not” K. Yes, I'm still not really getting the hang of this.

Because strong rhetoric is an expression of strong feeling, in this time of decadence we eschew it, because expression of strong feeling seems artificial; so we grunt, we swear, we make up stupid words like woke and truthy, and consider ourselves sophisticated.

If all the speaker does is grunt, and swear, and whine, and call people names (polysyndeton), the listener might know that he's mad about something, but they are never sure what it is. Sooner or later they will conclude that the speaker doesn't know either. But good rhetoric, whether from a politician, a news reporter or a cannibal, always gives us something to chew on.

may 29, 2017; last edited may 31, 2017

Godine, 2016. 243 pages

Reviewed by T. Nelson

his one is pretty much the same as the one on rhetoric: lots of quotes from G.K.

Chesterton, Shakespeare, Thoreau, Macaulay, and many others illustrating metaphors

and similes. The goal again is to teach us by example.

his one is pretty much the same as the one on rhetoric: lots of quotes from G.K.

Chesterton, Shakespeare, Thoreau, Macaulay, and many others illustrating metaphors

and similes. The goal again is to teach us by example.

But unlike rhetorical devices, all metaphors are pretty much the same, like different types of wheat. Chapter titles include “The Use of Animals to Describe Humans,” “The use of Nature to Describe Language,” and so on. The book is a tidal wave of metaphors, a tsunami of similes that laps and splashes into every corner of literature.

But is Farnsworth's nosological classification scheme complete? What about implied metaphors, as in that previous question, which implicitly compares metaphors to diseases? As Farnsworth says, much of our language and thought is metaphorical. Studying metaphors more deeply could have been a chance to explore how humans think.

Or how about if I say “The categorization is not strong with this one.” Or when Peter Fonda says “Nothing can stop us now!” in Dirty Mary, Crazy Larry? These too are a sort of metaphor. In fact, almost every turn of phrase that suggests something else is in some sense a metaphor.

Here's a typical quote, picked at random. Farnsworth introduces it by saying “Or the quality of weather can represent the quality of an event, as by supplying pictures of turbulence.”

In a word, the damages of popular fury were compensated by legislative gravity. Almost every other part of America in various ways demonstrated their gratitude. I am bold to say, that so sudden a calm recovered after so violent a storm is without parallel in history. [p. 49, citing Burke]

Like all the quotes, this one is great, but what we really need is expert advice about what to avoid. For instance, he could have reminded us that the metaphor must be logically consistent. Or that flowery (or should I say kudzuy) metaphors like those here would nowadays be regarded as wasted words. The last two chapters, starting on page 204, make a good start, but the rest is learning how to make macaroni and cheese by eating samples of it cooked by a thousand different chefs.

Is that a good metaphor? Probably not, but durned if I know why.

jun 17, 2017; last edited jun 22, 2017